SpaceX: launching, landing and berthing into history

/Over the last few days, SpaceX launched a Falcon 9 rocket, delivered a Dragon cargo ship to the International Space Station and, as a bonus, successfully landed the first stage of the booster on a platform in the Atlantic Ocean. It's safe to say that this was one of the best weeks in the NewSpace company's history.

On April 8 at 4:43 p.m. EST (20:43 GMT), the Falcon 9 rocket soared into the late afternoon skies at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station. It carried the CRS-8 Dragon capsule—the first to launch since the ill-fated CRS-7 mission. It was a textbook launch.

A little over two minutes into flight, the booster's first stage had finished it's job and detached from the second stage, which fired and continued on to orbit. Then, the rocket did something the company has been trying for a while now: it turned around and slowed itself for a soft touchdown on an ocean-going platform.

This was the fifth attempt at landing on an Automated Spaceport Drone Ship. All the others failed in some way (although one attempt only failed because a landing leg didn't lock into place). This flight, however, succeeded. It was a long time coming for SpaceX, as they had been testing and refining this process for the better part of two years now—not including the Grasshopper tests in Texas.

The atmosphere at SpaceX's headquarters in Hawthorne, California, was electric. This was the second time one of their first stage boosters was successfully recovered—the first at sea.

SpaceX has said they need to be able to land on both solid ground and the drone ships because of the high energy launch requirements on some payloads, such as those heading to geostationary transfer orbit or escape velocity.

Elon Musk, the company's founder said the firm hopes to re-certify and reuse the booster on a flight as early as June.

As if that accomplishment wasn't enough, SpaceX still had a mission to complete: sending the Dragon cargo ship to the space station. Right about the time of the first stage landing, the second stage had made it to orbit and released the space freighter.

Over the next two days, Dragon caught up with the space station. Finally, early Sunday morning, the capsule conducted its final approach to the orbiting laboratory.

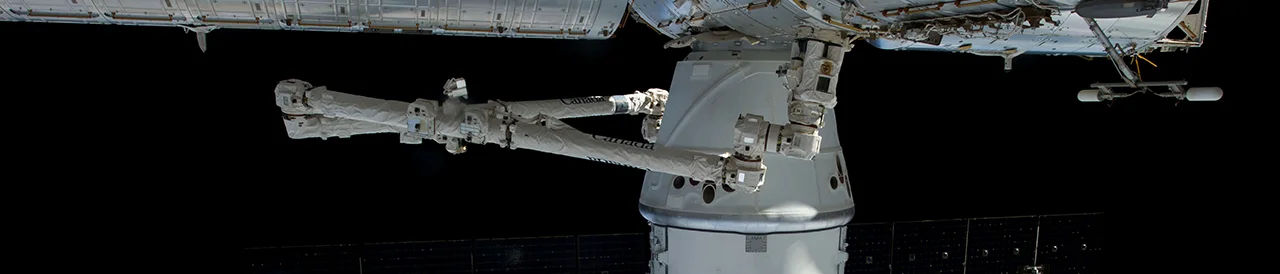

Capture by the space station’s robotic Canadarm2 took place at 7:23 a.m. EDT (11:23 GMT) April 10 about 250 miles (402 kilometers) above the Pacific Ocean just west of Hawaii. Controlling the arm was Expedition 47 Flight Engineer and European Space Agency astronaut Tim Peake. He, along with NASA astronaut Jeff Williams, monitored the approaching vessel from the Cupola window.

“It looks like we caught a Dragon,” Peake said after capture.

Then, over the next two hours, ground teams controlled the arm to move Dragon from its capture point just 33 feet (10 meters) below the station to the Earth facing port of the Harmony module.

The command to automatically drive four bolts in the Common Berthing Mechanism connecting Dragon and Harmony was given at about 8:55 a.m. CDT (13:55 GMT). The stations computer rejected the command at first, but upon trying a second time, it accepted and the spacecraft was officially berthed to the ISS at 8:57 a.m. CDT (13:57 GMT)—some 40 feet (12 meters) from the OA-6 Cygnus cargo ship attached to the Unity module. This marked the first time two commercial vehicles were at the station at the same time.

The arrival of Dragon also marked only the second time in space station program history that six vehicles were docked or berthed to the outpost. The last time was in 2011 when Space Shuttle Discovery was docked with the complex on mission STS-133—that orbiter’s final flight. That was also the only time all of the originally planned government-owned vehicles (Space Shuttle, Soyuz, Progress, Japanese HTV, and the European Space Agency’s ATV) were at the station at the same time.

This is the eighth Dragon to visit the space station. It is also the 84th uncrewed cargo ship and 170th overall mission to reach the orbiting laboratory.

The hatch between the cargo ship and space station will be opened early Monday morning. In the next three weeks, Dragon’s 7,000 pounds (3,175 kilograms) of food, supplies, and experiments will be unloaded and dispersed throughout ISS. Additionally, the vessel will be reloaded with trash and unneeded equipment to be returned to Earth.

On April 16, CRS-8’s most notable cargo, the Bigelow Expandable Activity Module will be robotically removed from the unpressurized trunk of the spacecraft and attached to the aft port of the Tranquility module. It will be expanded sometime in late May.

Dragon is expected to remain attached to the space station until May 1 of this year (2016).

Time lapse of the NASA TV feed of the rendezvous, grapple, and berthing of the SpaceX Dragon CRS-8 spacecraft to the Harmony module. Timelapse courtesy of Trent Faust, Video courtesy of NASA TV