Artemis 1 core gets an engine, more SLS cores to be ordered

/NASA’s first Space Launch System rocket recently received its first engine while the agency continues to work with Boeing to secure contracts for the giant vehicles through the end of the next decade.

Much like the Apollo program in the 1960s, the current Artemis program seems to have news every week. With fast-paced developments such as the announcement of very different bids from Boeing and Blue Origin for human-rated lunar landers, to updates for robotic precursor missions, the goal of a 2024 human Moon return seems more and more possible.

However, in order to literally get off the ground, NASA and contractor Boeing need to finish the long-delayed Space Launch System, or SLS, rocket. Last week it was announced that the first of four liquid hydrogen and oxygen consuming RS-25 engines were installed at the base of the first flight-worthy core stage, which will be used to send the uncrewed Artemis 1 mission on a multi-week journey around the Moon.

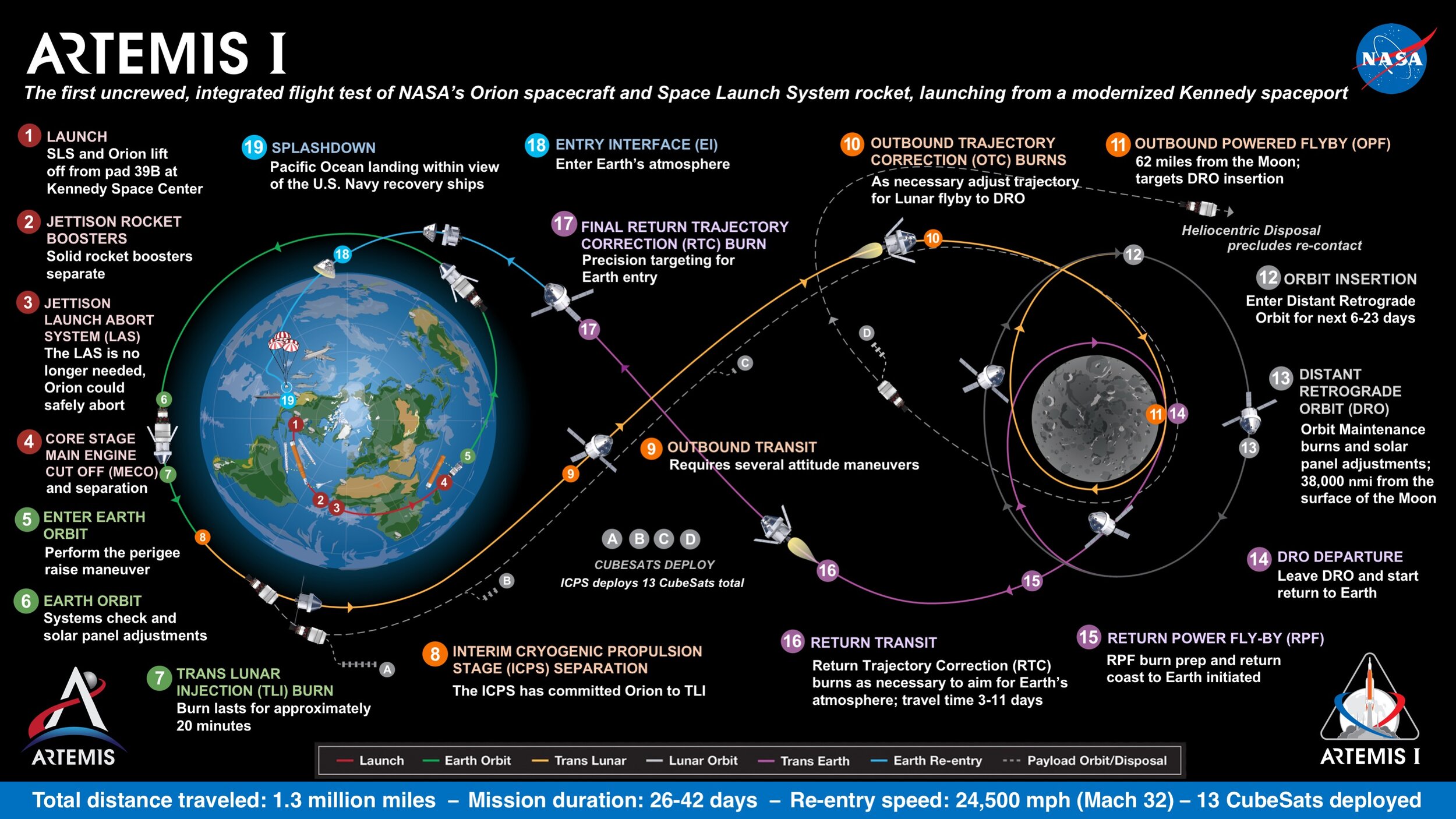

Artemis 1 is currently expected to launch in early 2021 and will send an Orion spacecraft on a 26-day flight. During its mission, the spacecraft will use its main engine to enter a distant retrograde lunar orbit before firing it again to return to Earth.

The rocket that will power this mission into orbit is nearly completed and almost ready for testing and systems verification. Currently, the core stage is at the Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans. The first RS-25 engine was installed in mid-October. The other three will follow in the weeks and months to come.

Once finished, the full 8.4-meter-wide, 65-meter-long stage will be loaded onto the Pegasus barge and be shipped to the Stennis Space Center in Mississippi where it will be attached to a test stand to perform a full-duration engine firing lasting about 8.5 minutes. This is known as the Green Run Test.

According to NASA, the SLS core stage is the largest rocket stage the agency has built since the Saturn 5 rocket stages during the Apollo program.

Once the Green Run Test has been performed, the stage will be placed back on the Pegasus barge to be shipped to the Kennedy Space Center in Florida to be integrated for launch with the other pieces of the Artemis 1 mission atop the Mobile Launcher in NASA’s Vehicle Assembly Building.

The other parts of the rocket include two five-segment solid rocket boosters, a launch vehicle stage adapter, an Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage, the Orion spacecraft and its launch abort system.

This infographic shows where the four engines will go on the first Space Launch System core stage. Credit: NASA

Meanwhile, on Oct. 16, NASA announced it intends to work with Boeing, the SLS prime contractor, to build as many as 10 core stages for the Artemis program. The agency said this would ensure the production of rockets through the end of the 2020s.

According to NASA, the new contract should include “substantial savings” compared to the first several cores of the SLS program that are being developed by applying “lessons learned” and “gaining efficiencies through bulk purchases.” The SLS program is years behind schedule and billions of dollars over budget.

Moreover, it is unclear if these are 10 additional core stages in addition to those for the Artemis 1 and 2 missions. However, NASA did say it has provided Boeing the initial funding to begin work on producing the Artemis 3 core in order to complete it in advance of the planned 2024 lunar landing.

“It is urgent that we meet the President’s goal to land astronauts on the Moon by 2024, and SLS is the only rocket that can help us meet that challenge,” said NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine in an Oct. 16, 2019, agency news release. “These initial steps allow NASA to start building the core stage that will launch the next astronauts to set foot on the lunar surface and build the powerful exploration upper stage that will expand the possibilities for Artemis missions by sending hardware and cargo along with humans or even heavier cargo needed to explore the Moon or Mars.”

NASA said this new contract is expected to support to 10 core stages and up to eight Exploration Upper Stages, also known as the EUS, which would evolve the SLS from its initial Block 1 version to the more capable Block 1B.

The Block 1 SLS, with an Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage, can loft about 95 metric tons into low Earth orbit or 26 metric tons into a trans-lunar trajectory. Once the EUS is available, those numbers increase to 105 metric tons and 37 metric tons, respectively.

Should the SLS ever evolve into a Block 2 variant, likely no earlier than the late 2020s, that rocket would sport upgraded solid rocket boosters with the potential to launch 130 metric tons to low Earth orbit and as much as 45 metric tons toward deep space destinations, such as Mars.

The first Block 1B SLS is expected to debut during the Artemis 4 mission in 2025, and could allow large cargo, such as future additions to the planned Lunar Gateway outpost, to fly to the Moon with the Orion spacecraft. Additionally, it could be used to send large science payloads deep into the solar system, such as what is currently planned for the Europa Clipper mission to Jupiter’s icy moon.

“The exploration upper stage will truly open up the universe by providing even more lift capability to deep space,” said Julie Bassler, the SLS Stages manager at Marshall, in a news release. “The exploration upper stage will provide the power to send more than 45 metric tons, or 99 thousand pounds, to lunar orbit.”