Starliner lands after abbreviated inaugural mission

/Some 48 hours after an internal clock error prevented the uncrewed Orbital Flight Test Starliner spacecraft from entering the correct orbit to get to the International Space Station, the capsule was commanded to return to Earth.

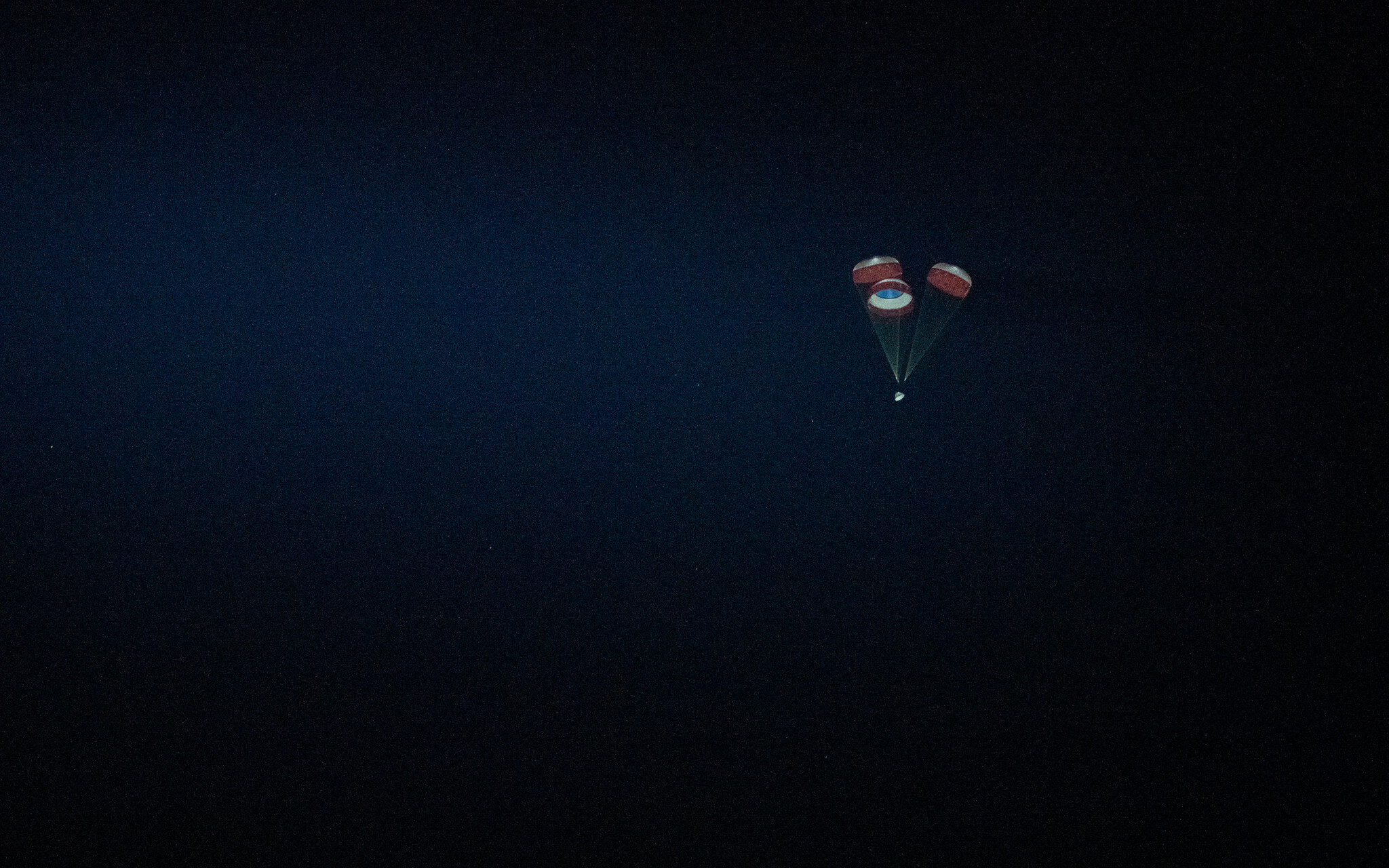

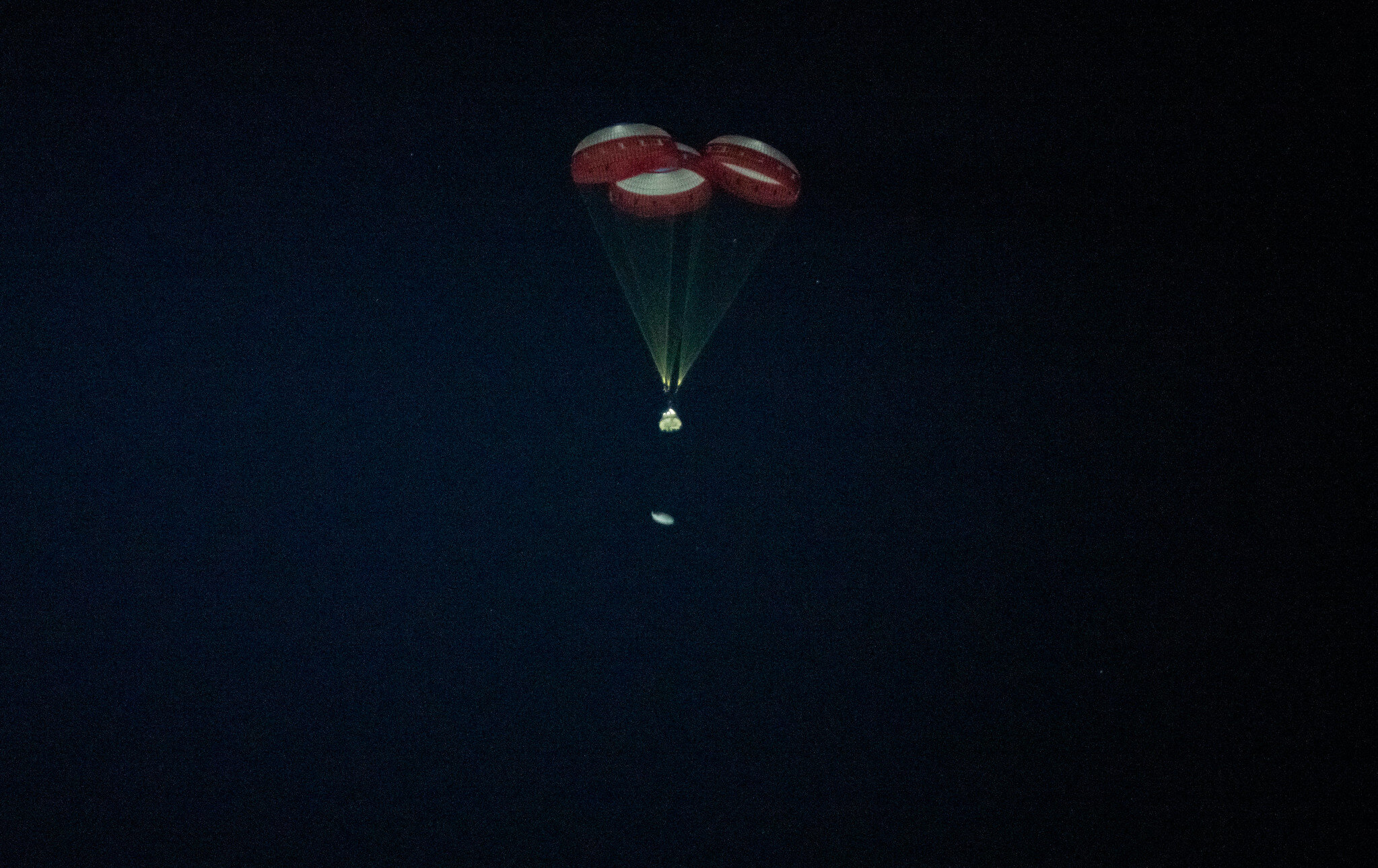

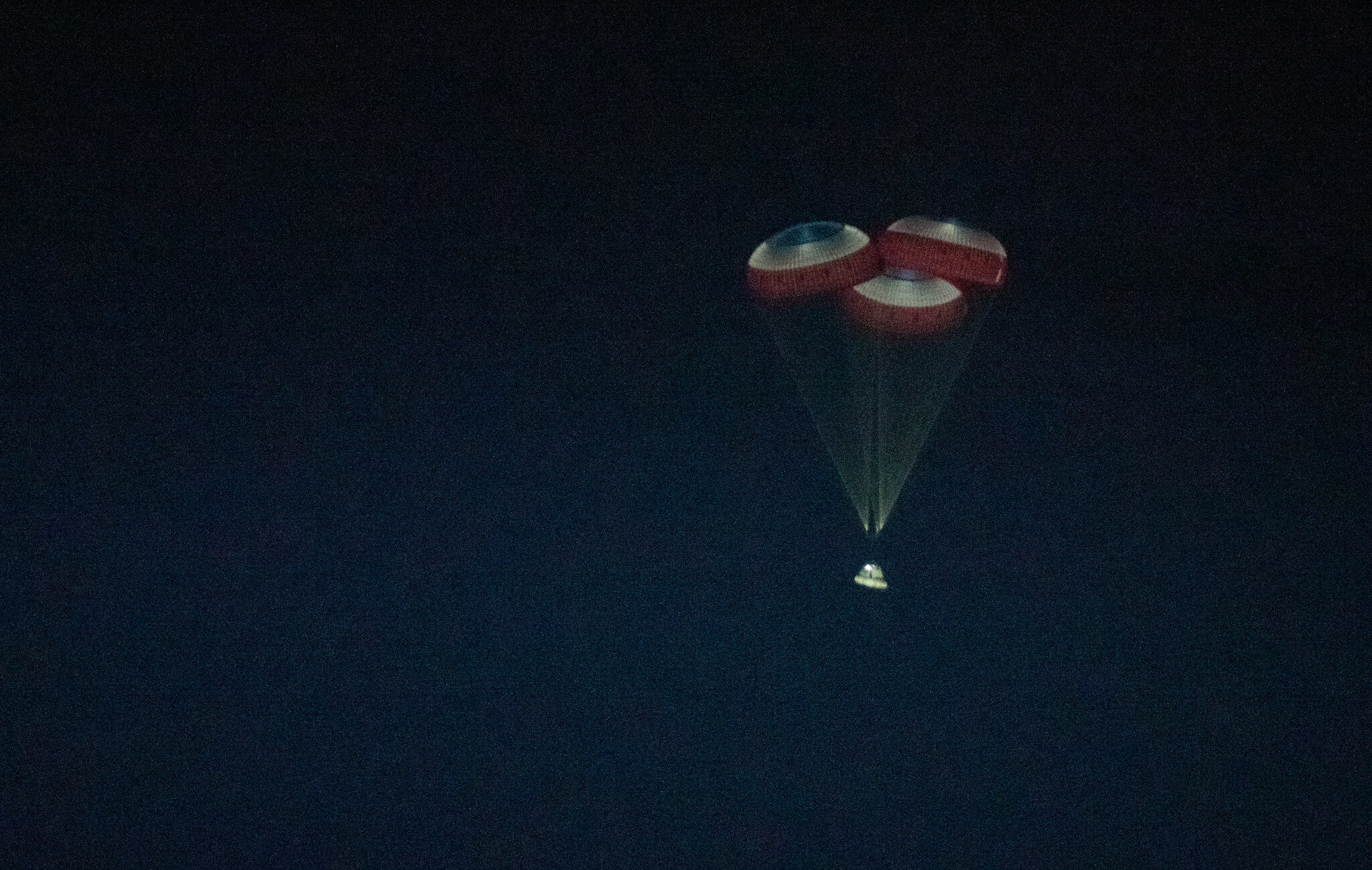

Starliner landed at 12:58 UTC Dec. 22, 2019, at White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico. Using a combination of parachutes and airbags, the capsule gently touched down just before sunrise.

“Today’s successful landing of Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner spacecraft is a testament to the women and men who have dedicated themselves to ensuring Starliner can safely transport crews to low-Earth orbit and back to Earth,” said Boeing Senior Vice President of Space and Launch Jim Chilton in a NASA news release. “The Starliner Orbital Flight Test has and will continue to provide incredibly valuable data that we, along with the NASA team, will use to support future Starliner missions launched from and returning to American soil.”

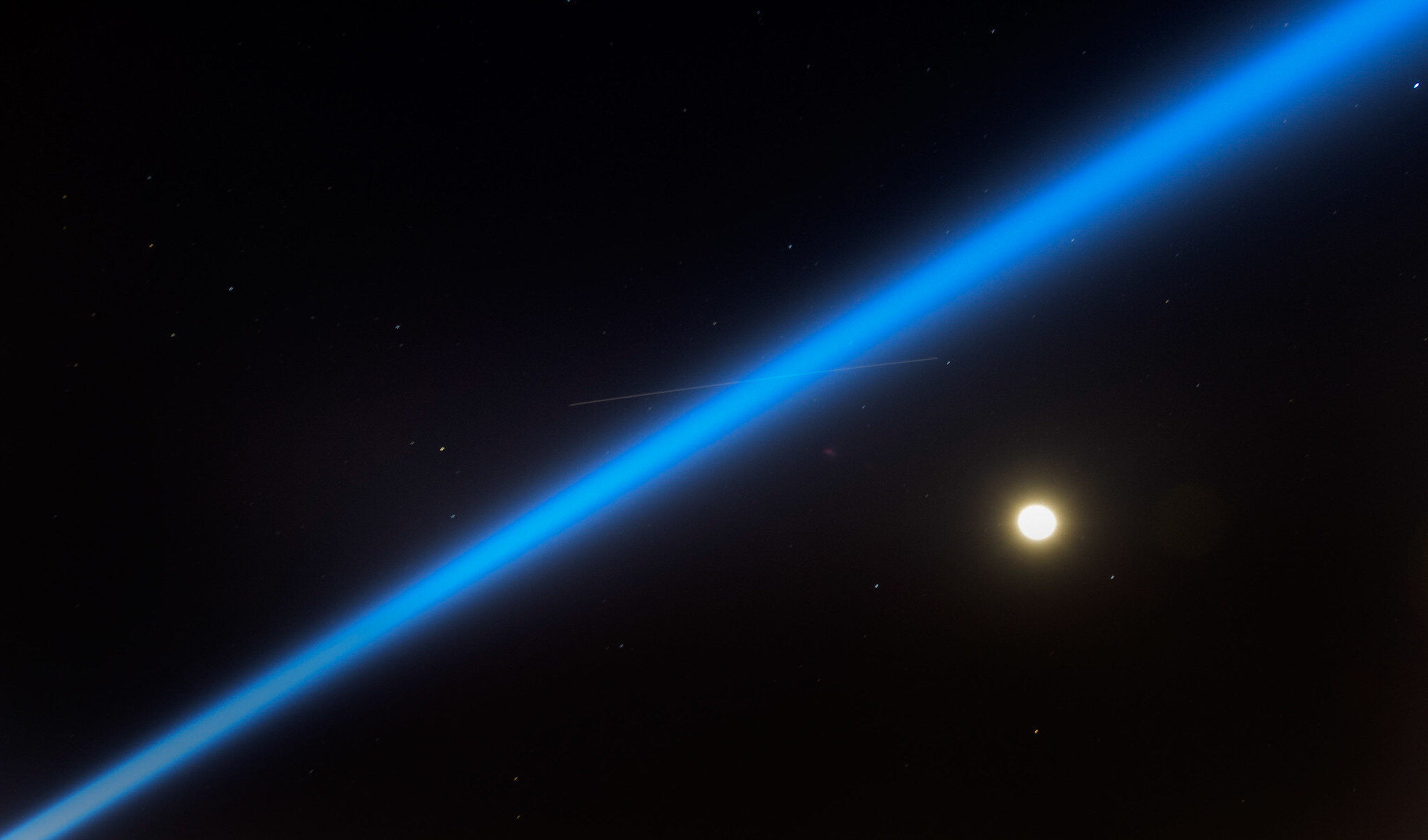

Shortly after separation from the Atlas 5 rocket during its Dec. 20 launch, the Starliner spacecraft experienced an “off-nominal” orbital insertion. For some reason, the uncrewed spacecraft received the wrong setting for its internal Mission Elapsed Timer. As such, upon separation, the vehicle thought it was at a different point in its orbit and did not initially perform its orbit insertion burn. Boeing is still investigating why this happened.

Teams on the ground noticed this and tried to send an override command, but because of an incorrect spacecraft orientation (likely due to the mission elapsed timer issue) the vehicle wasn’t able to establish a firm data link with NASA’s Tracking and Data Relay Satellites in a higher orbit.

Eventually a positive link was established and an orbital insertion burn conducted, but it resulted in placing Starliner in a much lower orbit of around 250 kilometers. All of the additional maneuvering at less-than-ideal places in its orbital path meant it used more fuel than planned, enough to preclude any docking attempt at the International Space Station, which is at a much higher, 400-kilometer orbit.

Originally, the Orbital Flight Test mission was to dock with the ISS on Dec. 21 to spend a week at the outpost before returning to Earth on Dec. 28. This would have showcased a full end-to-end test of the commercial crew spacecraft.

While Starliner was not able to demonstrate its ability to autonomously rendezvous and dock with the ISS, it was able to test a number of the Orbital Flight Test’s mission objectives. According to Boeing, these include, but are not limited to:

Testing engines for orbital adjustments

Testing the guidance, navigation and control hardware

Observing a positive performance of the spacecraft life support system

Station keeping demonstrations

Proving the vehicles docking mechanism can extended for docking

The final objective of the Orbital Flight Test was to prove the vehicle can land safely after leaving orbit. While Boeing still needs to go over all the data, Starliner appeared to land as planned.

At 12:23 UTC, it performed a 55-second deorbit burn. About two minutes later, the vehicle’s service module separated (it is not designed to survive reentry).

Once Starliner entered the atmosphere, friction slowed the spacecraft down to allow for a number of critical landing events. Several minutes before landing, a series of parachutes fired, culminating in three main chutes, to slow the capsule to about 30 kph. Additionally, the heat shield separated to allow the airbags to deploy.

Just before touchdown, the airbags inflated. These cushioned the impact with the ground, which will ensure future astronauts riding Starliner will enjoy a softer landing.

It’s unclear if the next Starliner mission will be the originally-planned Crew Flight Test or if NASA will require some sort of re-flight of the Orbital Flight Test mission.

Whenever the Crew Flight Test does happen, currently planned for the first half of 2020, it will see NASA astronauts Michael Fincke and Nicole Mann, as well as Boeing astronaut Christopher Ferguson, fly to the International Space Station for several months.

This was Boeing’s first orbital flight of its Starliner spacecraft to prove out the system to eventually send people to the International Space Station under the Commercial Crew Program.

Another company, SpaceX, is also working to send astronauts into space using its Crew Dragon spacecraft. It’s vehicle already flew its first end-to-end test flight to the ISS. This occurred in March 2019.

Both companies are behind schedule, but both expect to fly their crewed test missions in the first half of 2020.

NASA’s Commercial Crew Program was established in 2010. Ultimately, SpaceX and Boeing were the two companies selected and the U.S. space agency awarded up to $2.6 billion and $4.2 billion, respectively, to develop the two spacecraft.

Each company is contracted to send astronauts to the space station on up to six official crew rotation flights, which are expected to begin as soon as the spacecraft are fully certified.

Whichever company flies crew first, it’ll end the longest gap in the United States’ ability to independently send humans into orbit. The previous record was roughly 68 months between the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project in July 1975 and the first flight of the space shuttle in April 1981.

The current gap is now more than 100 months as of December 2019. In the interim, U.S. astronauts have been riding into orbit via Russia’s Soyuz spacecraft.

Once Boeing and SpaceX are certified to fly crew rotation missions, Boeing plans to refurbish the OFT capsule and use it to launch NASA astronauts Sunita Williams and Josh Cassada as well as European Space Agency astronaut Thomas Pesquet and a yet-to-be-named Russian cosmonaut. That liftoff is tentatively planned for late 2020.

Williams, the spacecraft’s planned commander, named her ship “Calypso” after a research vessel used by the oceanographer Jacques Cousteau.

“I love what the ocean means to this planet,” Williams said. “We would not be this planet without the ocean. There’s so much to discover in the ocean, and there’s so much to discover in space.”