Starliner's Orbital Flight Test mission 'go' for launch

/After years of development, the first orbital flight of Boeing’s Starliner is imminent. This uncrewed test is slated for a week-long trip to the International Space Station.

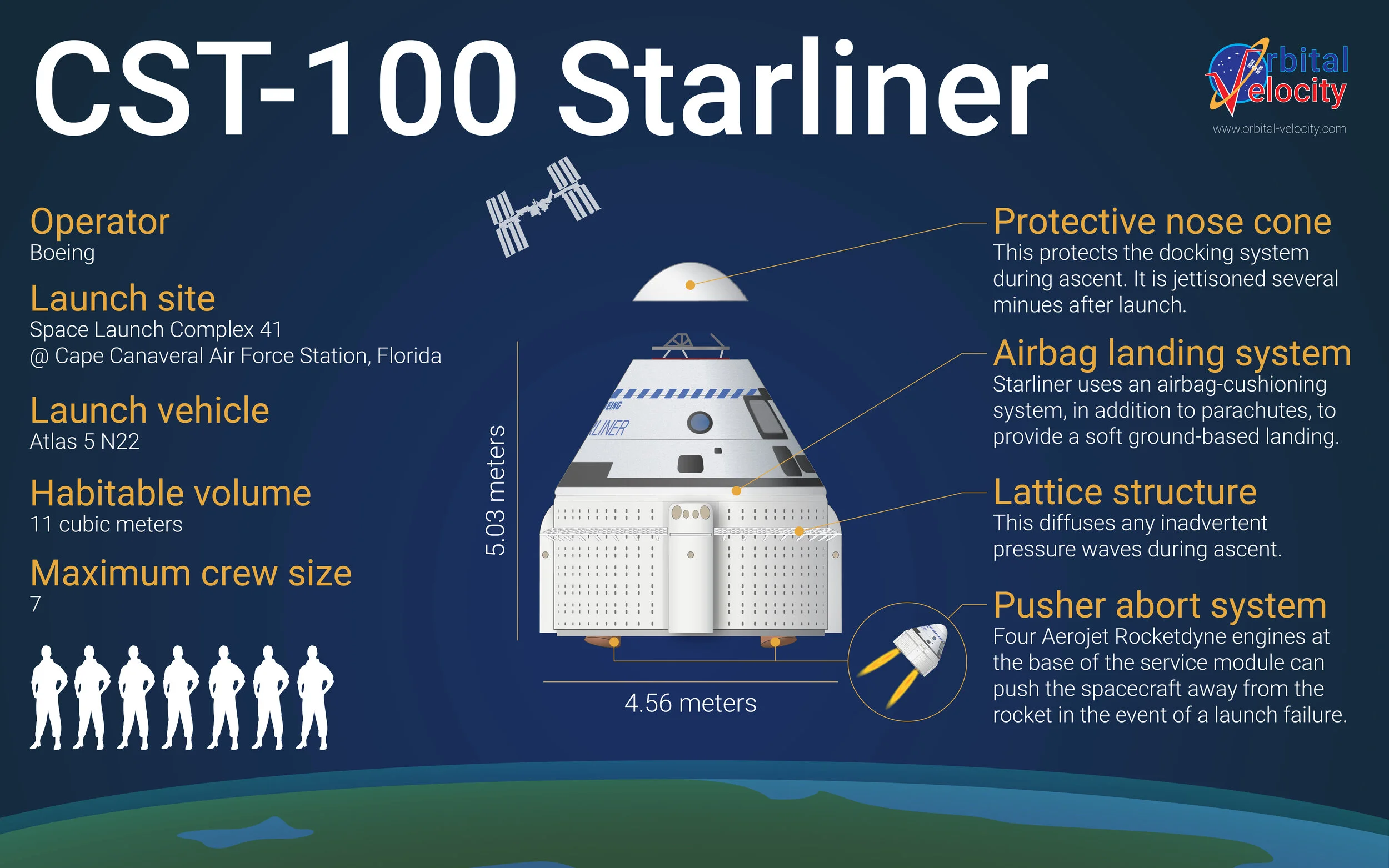

Starliner’s Orbital Flight Test, or OFT, is expected to take to the skies at 11:36 UTC Dec. 20, 2019, from Space Launch Complex 41 at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida. The purpose of this flight is gather end-to-end performance data of the Atlas 5 rocket, the Starliner spacecraft, both on the ground and in space, as well as docking and landing operations, according to United Launch Alliance, Boeing and NASA.

Ultimately, this data is expected to be used to certify the Starliner spacecraft to fly people to the space station as early as the first half of 2020 with regular crew transportation flight occurring soon after.

In a flight readiness review on Dec. 17, NASA and Boeing officially approved the Friday morning launch. The weather is only expected to have a 20% chance of violating flight constraints, with the primary concerns being cumulus clouds and ground winds.

Temperatures for the pre-dawn launch are expected to be roughly 17 degrees Celsius with winds at 25 kilometers from the east northeast.

The vehicle it is launching atop is a special variant of a United Launch Alliance Atlas 5 rocket called the “N22,” which means it has no payload fairing, two strap-on solid rocket motors and a dual-engine Centaur upper stage.

There are two other features required for an Atlas 5 to launch a Starliner spacecraft, an ascent cover and an aerodynamic skirt. The ascent cover protects critical hardware on Starliner, such as the docking mechanism while the aerodynamic skirt helps enhance stability while minimizing the loads on the vehicle, according to United Launch Alliance.

Once the rocket leaves the pad, the two boosters and the RD-180 engine on the launch vehicle’s core work to accelerate Starliner out of the lower atmosphere. After liftoff, the stack is expected to roll to place the spacecraft in a “heads up” position while throttling the core’s engine to limit the acceleration to 3.5 times the force of gravity.

Just over a minute into flight, the Atlas 5 is expected to reach the speed of sound. Roughly a minute later, the two solid rocket motors should finish burning and fall away as planned.

At 4 minutes, 29 seconds, the core should finish its job and separate to allow the dual engine Centaur upper stage to continue the process of sending Starliner into orbit.

The ascent cover is expected to be jettisoned at 4 minutes, 41 seconds into flight while the aerodynamic skirt falls away roughly 5 minutes, 5 seconds after liftoff.

Burning for some seven minutes, the Centaur upper stage is planned to place Starliner into an “elliptical suborbital trajectory” toward the space station. Once the spacecraft separates — about 15 minutes after launch — it’ll use its own engines to finish the job of getting into a full orbit.

From there, Starliner is scheduled to begin adjusting its orbit to catch up with the ISS and line up for docking. This is expected to occur at 13:27 UTC Dec. 21, assuming a Dec. 20 launch.

Starliner is planned to remain at the ISS until Dec. 28. During that time, the crew is expected to open the hatch and enter inside, collect roughly 270 kilograms of crew supplies and equipment. Also aboard is an anthropometric test dummy named Rosie the Rocketeer — a nod to the Rosie the Riveter character from World War II.

If the current schedule holds, Starliner is slated to undock from the outpost at 5:44 UTC to begin the process of returning to Earth. This will ultimately involve a deorbit burn several hours after departing the ISS.

Once the deorbit burn occurs, the spacecraft is slated to reenter the atmosphere and parachute down to White Sands, New Mexico. The landing is designed to incorporate airbags to cushion the touchdown, expected at roughly 10:47 UTC Dec. 28 under the current schedule.

This flight comes more than a month after Boeing’s pad abort test in White Sands. After the OFT mission is complete, NASA and Boeing will go over the collected data and prepare for the Crew Flight Test in the first half of 2020. That flight is expected to see NASA astronauts Mike Fincke and NIcole Mann, as well as Boeing astronaut (and former NASA astronaut) Christopher Ferguson, fly to the space station.

The CFT crew is expected to stay at the ISS for several months before returning to Earth. However, it is unclear if they’ll officially be part of the space station’s expedition crew.

Depending on scheduling, the CFT flight could be the first or second orbital human spaceflight from U.S. soil since the end of the Space Shuttle Program in 2011. SpaceX is also expected to fly people aboard its second Crew Dragon mission sometime in the first half of 2020.

Whichever company flies crew first, it’ll end the longest gap in the United States’ ability to independently send humans into orbit. The previous record was roughly 68 months between the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project in July 1975 and the first flight of the space shuttle in April 1981.

The current gap is now more than 100 months as of December 2019. In the interim, U.S. astronauts have been riding into orbit via Russia’s Soyuz spacecraft.